Ashford Artist of the Month – Mar 23 – Karen Selk

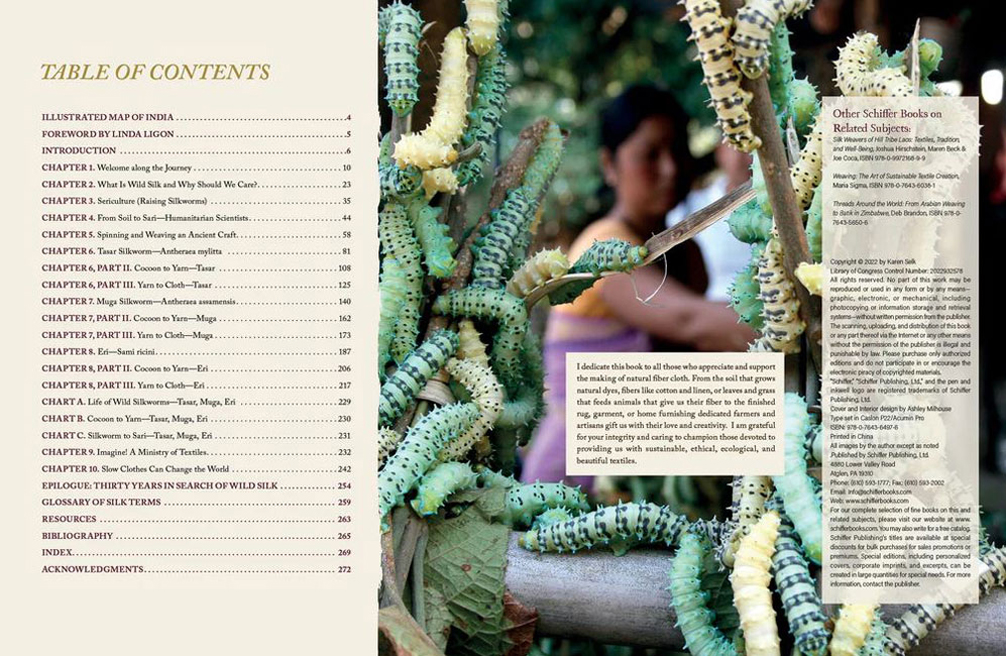

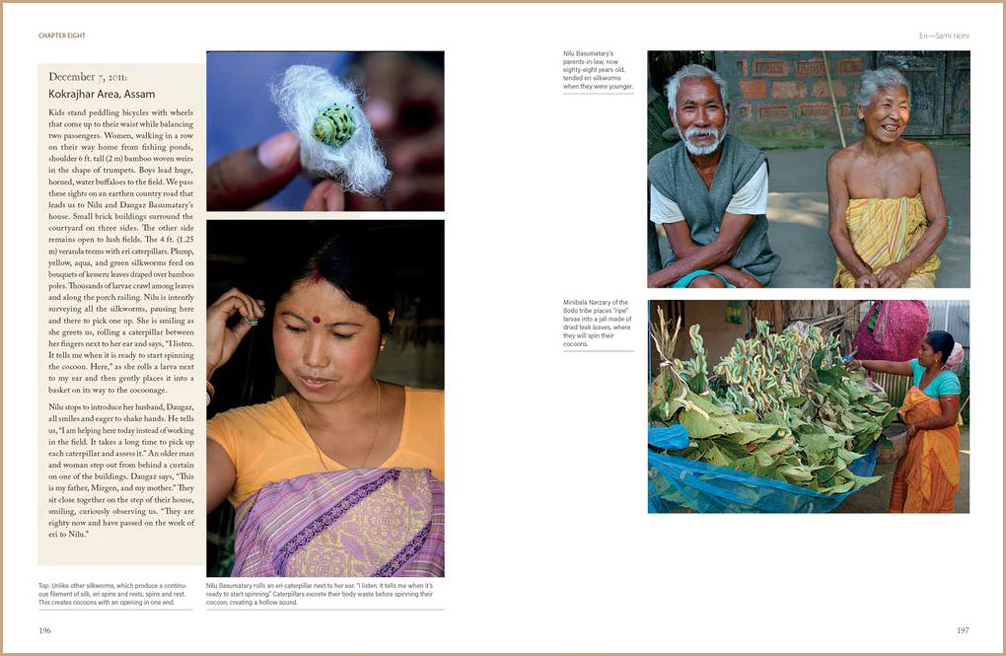

Karen Selk, weaver, teacher, lecturer, and author has, over thirty years, studied the raising of wild silkworms in the remote forests of central and eastern India. Her book In Search of Wild Silk, exploring a village industry in the jungles of India, has just been printed.

As a talented and experienced textile artist Karen has been involved in all aspects of raising silkworms and to spinning and weaving beautiful garments in silk. From this unique position she takes the reader on the miraculous journey of metamorphosis from caterpillar to silken luxury. But Karen also shows how wild silk is also tightly woven to an ancient living culture.

With over 300 photos and anecdotes from weavers, spinners, and silkworm rearers, readers will appreciate the love and dedication involved in each part of the process from soil to sari.

This is a beautiful book for all those with a passion for the luxurious silk fibre, textile arts, and traditional sericulture.

Kate

Karen Selk

All things silk have provided Karen Selk with a thread that binds together travel, research, writing, artwork, educating and managing a successful silk business. Her passion to learn about everything silk has led her througfhout Asia and the wild silk forests of India in particular for more than 35 years.The culmination of her field research has just been published in her new book: In Search of Wild Silk: Exploring a Village Industry in the Jungles of India. She lives in the Salish Sea on Salt Spring Island, BC, Canada where the serenity and beauty of island life inspire many hours in the studio and garden creating art, writing and growing organic food.

Everything about wild silk is captivating, exotic and full of heart. Raising wild silk – tasar (tussah), muga and eri is tightly woven to the ancient traditions and livelihood of the Adivasi (indigenous) people in the remote forests of central and northeast India. Village men and women unravel cocoons to make yarn and weave cloth in textured, rich earthy tones of beige, gold, umber, and papyrus. I have been researching in the field in India for over 30 years gathering photos and stories from the rearers, spinners and weavers to share their intimate connection to this vital and sustainable industry in my new book: In Search of Wild Silk: Exploring a Village Industry in the Jungles of India.

Raising Wild Silk

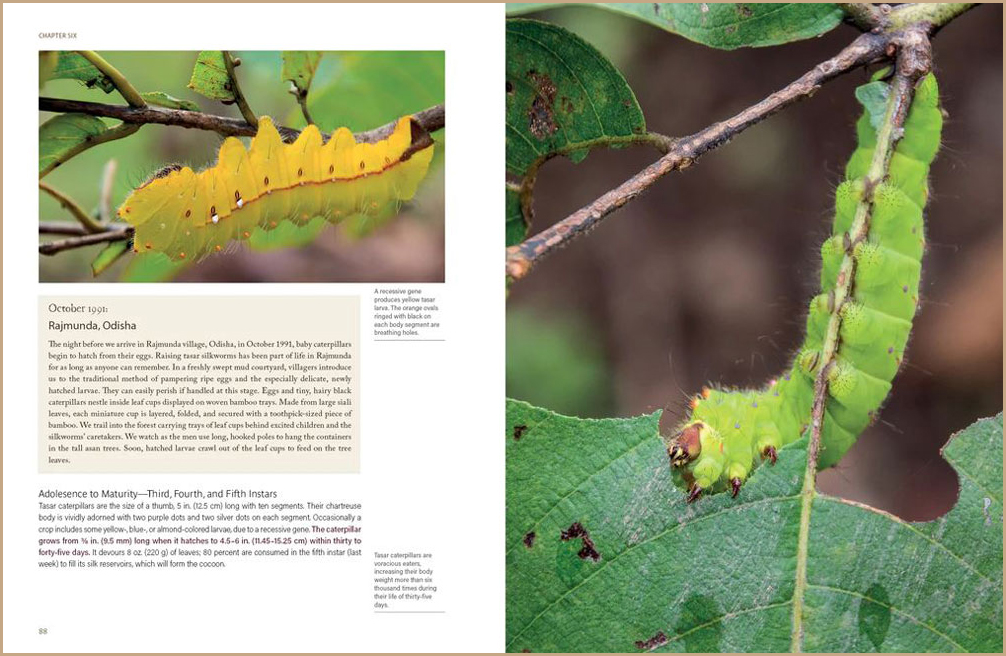

Wild silkworms prefer to be on the go in search of their own food leaves outside in the forest, rather than being fed on trays like the white Bombyx mori silkworms that eat mulberry leaves. The rearers (farmers) are out in the forest day and night using their sling shots, bows and arrows and noise makers to protect the caterpillars from birds, snakes, lizards and other predators, for their lifecycle of thirty to forty-five days. The silkworms eat non-stop, so their caretakers must keep watch and move them from a tree denude of leaves to another full of leaves. They are vulnerable to wind, rain, hail, fog and a score of diseases. Even with round the clock dedicated care of the rearers, the mortality rate is 50-80%. Still, wild sericulture (raising of silkworms) continues to provide a sustainable, healthy lifestyle, preferred by many.

Cultivating wild silkworms has changed dramatically in the more than thirty years I have been visiting rearers. From an era of age-old beliefs in evil moths bringing disease, rearers now embrace scientific knowledge. It has taken patience and mutual trust, but the silk custodians can see the benefits of adopting scientific methods introduced by scientists from the government Ministry of Textiles. They are now checking the mother moths with microscopes for deadly disease which wipes out a crop in one day and planting tens of thousands of food trees. The merging of traditional wisdom with a scientific approach is revitalizing this once declining and important industry as silk workers profit from increased crops.

-

- Female eri moth’s wingspan is 13 cm (5 in.). Her huge body carries 300-350 eggs. She attracts a male moth by emitting a sexy pheromone which he finds irresistible

-

- A female tasar moth carries 150-250 eggs in her body. Her wingspan is the width of your outstretched hand, about 18 cm (7 in.). The circles (ocellus) in the wings are see-through, like dragonfly wings. The colour of the circles changes with what is behind the mother – blue sky or green leaves

Making Yarn from Wild Silk

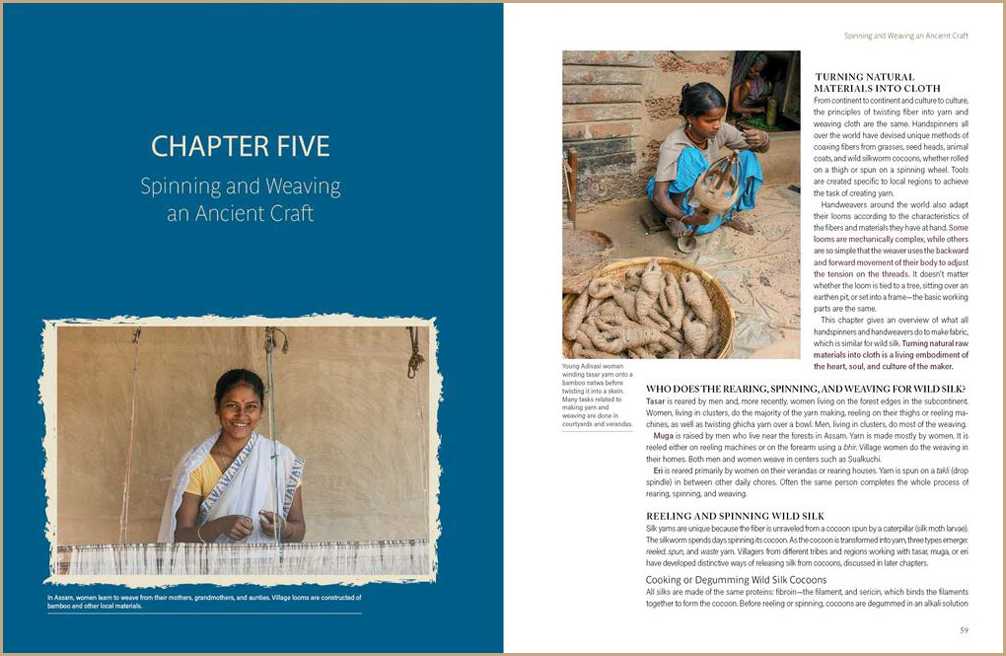

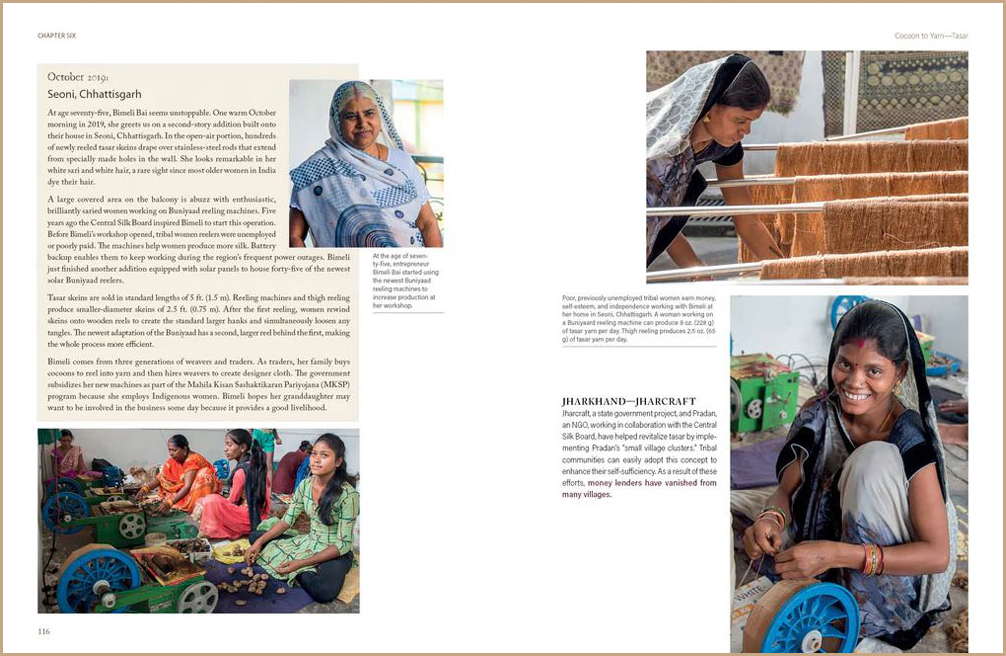

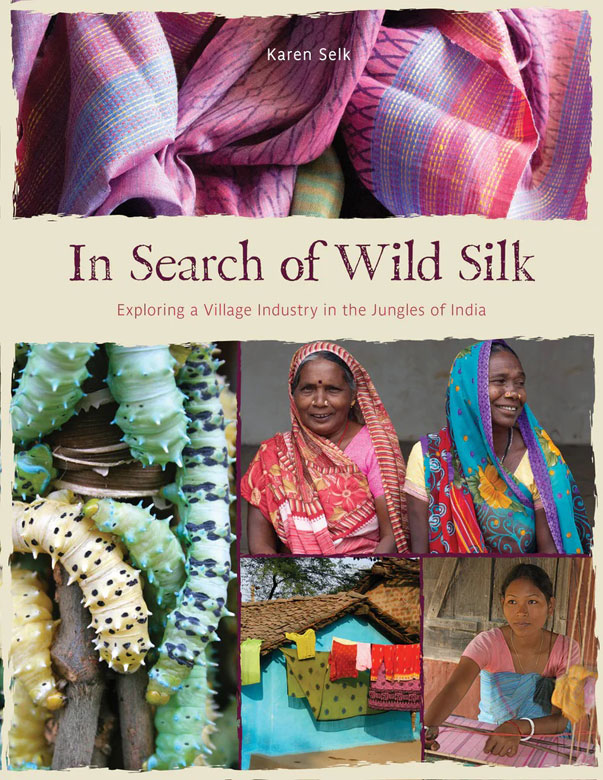

Yarn making for all three types of silk is done by women. The traditional method of unraveling the tasar cocoon is done by thigh reeling. Women take the filaments of 8 -10 softened cocoons and roll them against their thigh to make the highest quality reeled yarn. Silk left over from this process is used to make a second quality of spun yarn by rolling the fibres across an over-turned clay bowl. Women have devised a unique two-person method of forearm reeling to coax the delicate silk from the muga cocoons. The two women sit facing each other. One finds the filaments of 8 – 10 cocoons from a basin of warm water. She passes them to the woman in front of her. She takes the filaments in her left hand and rolls them over her right forearm, simultaneously pushing the wheel of a simple bhir to wind the yarn around a large bamboo bobbin. Eri silkworms spin awhile and stop, repeating this motion for three days. It results in an open-ended cocoon with a hole in the end. It cannot be unraveled like other cocoons. Its short fibers are teased into a cake and spun on a takli drop spindle in between other chores.

-

- Until the twenty-first century, the slow process of thigh reeling was the only way village women could transform tasar cocoons into yarn. This woman can thigh-reel fifty to sixty cocoons per day producing 60-80 g (2-3 oz.) of yarn

-

- This woman is holding a simple cross-shaped tool, called a distaff. The distaff prevents the eri fibre from tangling while spinning on a takli, drop spindle

Weaving Wild Silk

In tasar regions, men do most of the weaving on pit looms which are dug into an earthen floor. The treadles are in the pit. Men sit on the floor operating the peddles in the pit. In the villages of Assam where both muga and eri are raised, women do the weaving on simple frame looms on their verandas.

The revitalization of working with wild silk addresses many of the concerns we so desperately need help with, right now, to heal our planet and social fabric.

Raising wild silk is a sustainable occupation, centered around family and community with a deep connection to the land. It is labour-intensive boosting employment for millions of rural Adivasi people and restoring the environment through the planting of trees and intercropping. Increased income means the younger generations are remaining in their communities rather than migrating to overburdened urban areas and preserving their culture. A glimpse into wild silk will provide appreciation of where our fabric comes from, who makes it and why we should care.